Are you tired of just using programming languages for work, without knowing how it works? Do you want to know what’s happening inside the machine, after you’ve finished writing your code?

Well, you are not the only one. And you will know everything about it after reading this article.

As it turns out, there are three concepts, each extremely close to the others:

- How a programming language works, from the inside.

- How a Compiler works.

- How to build a new programming language.

Ultimately, I think the third point is what every curious student like us is interested in. So, we are in luck that these are all similar concepts!

How to build a new programming language

Let me start with a funny question for you. According to Google, there are about 26 Million software developers in the world. How many of them do you think would know how to create a new programming language?

Very few of them, I bet. In fact, I didn’t receive a training about it when I was a college student.

The reason is that very few developers are real computer scientists, and even among the latter group, only few of them have studied formal languages and compilers.

Programmers are practical people: Does it compile? Does it seem to work? Okay, then push.

Few coders have been trained to think formally. Additionally, creating a programming language is a task much closer to science and art, than to pure coding (although, of course, a lot of coding is needed too).

And yet, it teaches so much! There are so many fascinating steps involved, and opportunities to learn about:

- High level software engineering,

- Advanced algorithms and data structures,

- Programming patterns,

all of which are certain to be extremely useful during the career of a developer. And a computer scientist. And a software engineer.

Steps to create a programming language

From a very high perspective, creating a new programming language involves three main steps.

- Define the grammar.

- Build the front-end compiler for the source code.

- Build the back-end code generator.

So, you start with a pen and a piece of paper where you define the Grammar of your language. If you don’t know what a Formal Grammar is, then just think about it as the grammar of a human language (and read my article about it).

For example, in a human language you might say “A sentence is made by an Article, a Noun, and a Verb”. Then, the natural ambiguity of the language, mainly given by the spoken part and by human nature, throws this rule away.

In a formal language, if your grammar says “Assignment is made by a Variable Name, the Equal (=) sign, and a Number”, then this will be the only way someone can instantiate a variable in the source code of a program, otherwise the code would not compile (or it would raise an error, in case you are building an interpreted language).

In short, the formal grammar defines what the source code of a program must look like, in this language. It’s about the syntactical rules that programmers will have to respect in order to write a program in your language.

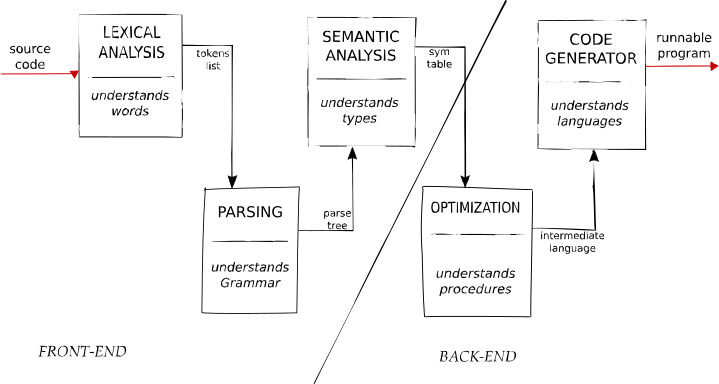

The Front-End Compiler is a piece of software that takes the source code and produces some weird looking data structure. More about this later in the article.

Finally, the Back-End Code Generator is another piece of software that takes whatever was produced by the Front-End and creates a code that can actually be run.

Wait. That… can be run? So this is all about taking the initial source code and making a new source code (that can be run)?

Yes. But one that the machine can understand, often called Target Machine Code. Strictly speaking, it means you should provide Assembly code as a result, give it to the Assembler that will work along with the Linker/Loader and then they will give back to you the machine code.

However, many savvy people have already gone through this effort in the past. Thus, very often new programming languages are just translated into existing programming languages, for whom a compiler already exists.

For example, while architecting your new language you may decide that your compiler, instead of generating machine code, generates C code that is then given to a C compiler. This is a standard approach and it will not take away from you any of the funny parts of writing a compiler: you will still need to build one.

But then, what does writing a compiler mean? Let’s see.

Steps to create a compiler for a programming language

Building a serious compiler for a complex programming language is a hell of a task. A large team full of skilled people is needed.

For instance, it took about 3 years for the FORTRAN 1 compiler. Built for scientific computing, the FORTRAN language was a game changer in the field and it is still widely used today. They did a good job and pretty much changed the history of computing.

Despite the scary complexity, compilers have just 5 main parts:

- Lexical Analysis. Recognize language keywords, operators, constant and every token that the grammar defines.

- Parsing. The stream of tokens is “understood”, in the sense that the relation between each pair of token is encoded in a tree-like data structure. Such a tree is meant to describe the meaning of the operations, in each line of source code.

- Semantic Analysis. Probably the most obscure of all steps. Mainly involves understanding types and checking inconsistency in the “meaning” of the source code (not just in the syntax). Tough.

- Optimization. No matter how good the source code was before compilation, chances are that while going to lower levels of encoding (till machine code) several optimizations can be implemented. Things like memory optimization, or even power-consumption optimization. And, of course, runtime optimization.

- Code Generation. The optimized version of the original code is finally translated into executable code.

Even though these five steps to create a compiler have not changed since a few decades, the complexity and time investment devoted to each of them have changed a lot.

The first compiler for FORTRAN was built from 1954 to 1957. At that time, all steps but semantic analysis were very involved and complex, which also explains why it took 3 years to come up with the result.

Nowadays, instead, a few steps have become almost automatic. If you define your own formal grammar, and you do it well, then you can use software that makes Lexical Analysis, Parsing and Code Generation automatically for you.

Today, teams that are building and maintaining a Compiler are mostly focused around the Optimization step. It has become extremely important, especially given the big advances in hardware. The Semantic Analysis steps is also fairly involved, although not nearly as much as the Optimization.

Let’s see more details for each step.

Lexical Analysis

This step takes off directly from the Formal Grammar.

Let’s say you want to build a language to represent minimalistic arithmetic operations. Your Grammar might look like the following:

program : [expression";"]*

expression : assignment

assignment : result "=" operation

operation : variable operator variable

operator : "+" | "-" | "*" | "/"

variable : "1" | "2" | "3" | "4" | "5"

| "6" | "7" | "8" | "9" | "0"

result : "L" | "O"This is really a poor example, but it’s useful for the sake of illustration. You can read the above grammar as:

A Program is made by zero or more Expressions followed by a semicolon (curly brackets means “zero or more” of what’s inside them). An Expression can only be an Assignment. An Assignment is made by a Result followed by an Equal sign, followed an Operation. An Operation is made by a Variable, followed by an Operator, then another Variable. An Operator must be a symbol among four choices: “+”, “-”, “*“, “/” (double quoted symbols are terminal tokens). A Variable must be a symbol among ten choices (the ten digits). And a Result must be either the “L” symbol or the “O” symbol.

If you pause now just one minute and think, you will realize that with this silly grammar one can only represent a sequence of additions, subtractions, multiplications and divisions between 2 small integers (from 0 to 9 included). The sequence may also be empty, and if it’s not then the elements in it must be separated by a semicolon. Oh, also, the result of each operation can only be named either “L” or “O”.

A valid “source code” might look like

O = 2 + 3;

L = 5 * 2;

…It’s dumb and you cannot do anything with it. But I can explain how the Lexical Analysis step works! Your Lexical Analyzer will go through the source code, and identify each token along with its type, according to the grammar. So the result of the Lexical Analyzer for the 2-liner above will be:

"O" - result

"2" - var

"+" - operator

"3" - var

"L" - result

"5" - var

"*" - operator

"2" - varIt should be easy to understand why there exist software tools that perform this task for any well-defined grammar. Actually, if you’ve done it manually once then it becomes boring to do it again.

Parsing

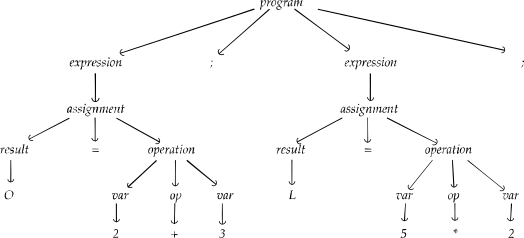

The Parser will take the list of tokens (output of the previous step) and create a tree-like structure, that is meant to describe the “meaning” of the source code. In the previous example (the silly arithmetic operations) the tree reflects the actual operations:

With some simplification, you can assume that the tree is not actually needed. Just knowing the leaves of the tree might be enough for the overall objective to compile the source code. At any rate, each parser may act differently but many of them do not store the actual tree in memory.

Semantic Analysis

If you are building a language with static types, or other nuances, then in this step you will want to check that the user is not doing anything stupid. Keep in mind that the user is also a programmer!

This step is very hard, in particular when it comes down to variables binding. Consider the following snippet in Python.

def foo(foo):

return foo + foo

val = 5

print(foo(val)) # >> 10

def foo2(foo2):

return foo + foo2

foo = val

print(foo2(7)) # >> 12This is clearly not good code. But let’s look at it more closely now.

Can you imagine what a mess is for the Python interpreter to understand what you are doing by naming your variables foo, a routine foo, the argument of this routine foo and of course, using the identifier foo inside the scope of the routine called foo.

Binding is about assigning the right value (5, 7, or even an entire function body) to the right identifier (foo, val, foo2), according to the current scope. Semantic analysis is about understanding if you messed up something.

Optimization

This step is a bit like editing a text after it’s been written by the original author.

However, each editor has their own objectives. So, as a code optimizer, your focus could be in reducing memory usage, or runtime. But it could also be to reduce the number of database access. Or to reduce power consumption, or network messages.

With so many specialized hardware, and so many different networks, databases, architectures, it’s no surprise that compilers can vary quite a lot how they optimize the code.

A special mention must go, in this subject, to the so-called Data Flow Optimization.

Every meaningful source code makes heavy use of aggregated data structures, such as arrays, that are accessed throughout the program. Data Flow Optimization is a term used to improve whatever the programmer did with data structures in his program, in order to make the overall execution more efficient.

Code Generation

The final step, informally named CodeGen, is also commonly automatized nowadays. In fact, translation from a parse tree to, potentially, any existing language is kind of a solved problem.

Still, there might be specific needs, or some innovation in your compiler, that convince you to build your own code generator. Most typically you would translate the parse tree either into Assembly code, or into C code that can then be compiled with an existing C compiler.

What’s next

When you complete the front-end compiler and the back-end code generator then you’re more or less ready to go. There exists a fun project on GitHub that is about creating a compiler for Lisp in every possible language (see the references at the bottom).

In my opinion, studying the theory of languages and compilers is worth the time it takes because it teaches so much about the real nature of one thing programmers use a lot: Programming Languages.

Also, it’s a good excuse to learn about parsing patterns, recursive descent algorithms, variables scope and bindings (which you should already know!). If you ever need an excuse to learn something.

As usual in engineering, the practical part is of utmost importance too. More on this in the next articles.

References

My article What is a Programming Language Grammar?

The Dragon Book. Compilers: Principles, Techniques and Tools. Wikipedia page (of the book).

Language Implementation Patterns. A book by Prof. Terrence Parr.

Alex Aiken’s class Compilers at Stanford University. Available as free MOOC online.

GitHub project mentioned in the article: https://github.com/kanaka/mal.